T4K3.news

Cuttlefish Demonstrate Self Control in Delayed Gratification Test

Common cuttlefish show delayed gratification in a test modeled on a child experiment, highlighting surprising cognitive skills in a solitary predator.

Common cuttlefish show delayed gratification in a task modeled on a child test, revealing cognitive skills in a predator with no social life.

Cuttlefish Demonstrate Self Control in Delayed Gratification Test

A study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B shows six common cuttlefish passing a delayed gratification task modeled on the Stanford marshmallow test. The animals learned to recognize symbols indicating immediate versus delayed rewards and chose to wait for a more desirable food when given the option. The test revealed that the cuttlefish waited up to 130 seconds for live shrimp instead of taking a smaller prize, suggesting planning and self control.

The researchers note that cuttlefish are solitary hunters, yet they display cognitive skills that align with behavioral flexibility and planning. The findings support the idea that intelligent traits can evolve in non social species, possibly linked to their ambush hunting style and the need to optimize prey selection. The study also connects this result to broader cephalopod cognition, including episodic like memory and potential false memories, underscoring a diverse landscape of intelligence in the ocean.

Key Takeaways

"Cuttlefish spend most of their time camouflaging, sitting and waiting"

Describes the behavior underpinning the test

"Delayed gratification may have evolved as a byproduct of this, so the cuttlefish can optimize foraging by waiting to choose better quality food"

Researchers' hypothesis about evolution of self-control

"Intelligence does not follow a single evolutionary path"

Implication drawn from the study

These results challenge the assumption that complex thinking follows a single path tied to social living. A predator that spends much time camouflaged could benefit from waiting for a better moment to strike, a signal that cognitive evolution can chase efficiency rather than social status. Yet the small sample size and lab like conditions invite caution about generalizing to wild populations. If further work confirms these patterns, it could reshape how we value cephalopod habitats and push policymakers to consider their cognitive lives in conservation plans.

Highlights

- Patience pays off in the deep

- Smart minds come in unlikely forms

- Wait for the better prey and you win the hunt

Conservation policy and public reaction risk

The findings touch on animal intelligence and conservation, which can provoke public debate, influence funding, and shape regulatory priorities.

The ocean keeps its own mind and science will keep listening

Enjoyed this? Let your friends know!

Related News

Peer promises boost preschool patience in online test

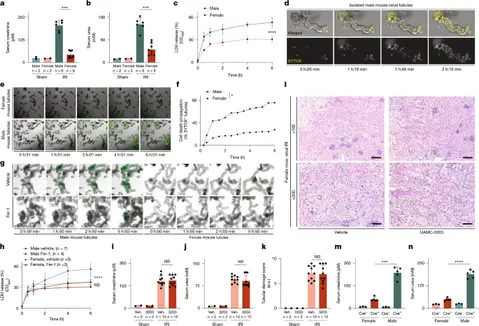

Estrogen protects kidneys from ferroptosis

Study reveals accuracy issues in medical self-testing kits

Psilocybin shows promise as an anti-aging treatment

Sinner reaches Cincinnati quarterfinals

Hookup Health on Campus

Shevchenko advocates for OnlyFans platform

HS2 bridge deck moved into place at night